This is part 2 of a 1, 2, 3 part BLOG series on this January 2020 two-day event featuring Dr. Vandana Shiva at UC Santa Cruz

Do public Universities have an obligation to present evidence-based information? Does freedom of speech extend to sponsoring speakers who spread misinformation and fear? These are important questions to ask in the current climate, and the answers must be true for all polarizing speech – irrespective of which side of the political spectrum it may fall.

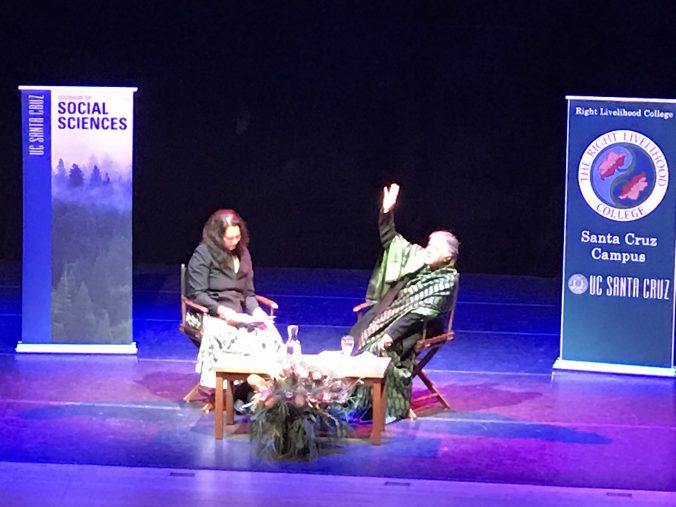

As someone who works in agricultural science, and is passionate about evidence-based policy, I attended a two-day event at UC Santa Cruz featuring Dr. Vandana Shiva in late January 2020. She was doing a speaking circuit around California Universities, and had preceded the visit to Santa Cruz with a visit to Stanford. Her visits were not without controversy. I attended the session at Santa Cruz to see for myself what all the fuss was about as detailed in Part One of this BLOG (Poison-free, fossil-free California agriculture) , and had some concerns regarding the factual basis of some of the claims made by Dr. Shiva.

One of the statements that Dr. Shiva made at the Sunday session entitled “Poison-Free, Fossil-Free Food & Farming” workshop was that citrus greening disease was not affecting organically-grown citrus plants. This plant disease kills citrus trees and has devastated the Florida citrus industry. It is carried by the Asian citrus psyllid which feeds on citrus leaves and stems.

The Asian citrus psyllid can spread the bacteria as the pest feeds on citrus trees and other plants.

This insect infects citrus trees with a bacteria that causes citrus greening disease also called Huanglongbing (HLB). HLB has been confirmed in California, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Puerto Rico, South Carolina, Texas, and US Virgin Islands.

The best way to protect citrus trees from HLB is to stop the Asian citrus psyllid, and this often involves spraying with synthetic insecticides which are not in compliance with organic standards. Once a tree is infected with HLB, it will die. Diseased trees need to be removed in order to protect other citrus trees on the property, neighbors’ trees and the community’s citrus. One hope is perhaps a genetically engineered disease-resistant tree will one day provide a solution to this problem.

However, Dr. Shiva claimed that “Soils rich in soil organisms are giving immunity to the plant. And even with the citrus failure, trees organically grown actually don’t get the disease” and she followed on to suggest that conventional trees get citrus greening disease because they are weak. Evidence please?

So do organic production methods protect citrus plants from citrus greening disease?

No. According to the organic center who have developed a helpful “Organic grower’s guide for combatting citrus greening disease, “Organic citrus producers have suffered terrible losses from citrus greening, and they need to be aware of organic solutions to ward off this disease,” said Dr. Jessica Shade, Director of Science Programs for The Organic Center. “Conventional and organic farmers alike have had their groves decimated by citrus greening,” she said. “While our report provides tools for them, to help them in their struggle, without more research we’ll continue to see a dramatic decline in citrus production – especially organic citrus.”

Another questionable statement Dr. Shiva made was that genetically engineered (GM) Bt cotton (which is protected from caterpillars by expressing a protein known as the Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) toxin which is toxic to caterpillars but not mammals) “results in farmers using more pesticides”. And to add some emotion to that statement she said she “had rushed to where 130 farmers growing Bt cotton had died from spraying pesticides”, with the implication being that this was because of the GM cotton. This claim makes really no sense.

The weight-of-evidence literature on insect-protected cotton is that Bt cotton farmers spray less insecticides, especially organophosphates (Multidecadal, county-level analysis of the effects of land use, Bt cotton, and weather on cotton pests in China; Bt cotton and sustainability of pesticide reductions in India; Impact of Bt cotton on pesticide poisoning in smallholder agriculture: A panel data analysis; Bt cotton cuts pesticide poisoning). If Bt cotton actually necessitated using more insecticides, then it might be reasonable to ask why would farmers plant Bt cotton?

Certainly there can be secondary pests that emerge when broad-spectrum insecticides are no longer sprayed on cotton, and there are some concerns with the development of resistance to Bt, especially given there were no refugia established in India as discussed in this article. But trade-offs exist with all pest control methods, and sometimes it seems that if there is a single trade-off associated with GM, and despite the documented benefits that are suggested by its widespread adoption, this tradeoff is used as a “gotcha” to dismiss all uses of this breeding method, in all situations. A common example is some weeds have developed resistance to glyphosate when used indiscriminately, therefore all GMOs are bad.

More generally the US National Academy of Sciences report on GM crops found “There is “reasonable evidence that animals were not harmed by eating food derived from GE crops,” and epidemiological data shows no increase in cancer or any other health problems as a result of these crops entering into our food supply. Pest-resistant crops that poison insects thanks to a gene from the soil bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) generally allow farmers to use less pesticide. Farmers can manage the risk of those pests evolving resistance by using crops with high enough levels of the toxin and planting non-Bt “refuges” nearby.” This 800 plus page NAS study drew on hundreds of research papers to make generalizations about GE varieties already in commercial production.

Unfortunately Dr. Shiva made no reference to weight-of-evidence studies in her presentations, nor the consensus statements of scientific societies. Rather she frequently drew on anecdotes, appeals to “nature” and emotion, and an occasional reference to a selected subset of the scientific literature to support her points, including the much criticized and ultimately retracted highly-controversial 2012 Seralini study (subsequently republished in a different journal) to suggest GMOs and glyphosate were associated with tumors in rats, and a 2014 Sri Lankan paper that posed an untested hypothesis that glyphosate was responsible for chronic kidney disease of undetermined causes (CKDu). A systematic 2018 review and meta-analysis “found little evidence that pesticides were the main cause of CKDu in Central America.”

During the Sunday workshop, Dr. Shiva stated that “I am not an agricultural scientist. I am not a toxicologist. I am just in deep love with the Earth.” This was met with approving nods and applause by the Santa Cruz audience. By setting up this dichotomous framing – that scientists with a deep understanding of agriculture and toxicology are somehow not in love with the Earth, her message seemed be to distrust expertise and science, and rather side with people who profess “a deep love of the Earth”. My land grant colleagues spend careers trying to use science to develop approaches to decrease the environmental impact of agriculture to help both the earth and humanity. If agricultural scientists and public sector toxicologists are the enemy to be despised or ignored, then I fear for the future of food production.

Students from Stanford University invited Dr. Shiva to speak at that University the Thursday (1/23/2020) prior to her appearance at Santa Cruz . Following the controversy regarding that event, the student group “Students for a Sustainable Stanford” (SSS) wrote in their campus newspaper:

“We recognize that Dr. Shiva has made many incendiary statements in her career. Some of them are untrue. For example, she has argued that farmer suicides in India have doubled since the introduction of Bt cotton, and that GMOs are unsafe to consume. She referenced these points during the lecture. These stances are not supported by the scientific literature, and our organization does not endorse them. Do these statements delegitimize Dr. Shiva’s entire platform? Should she be denied the microphone because some of her statements have been disproven?” No. SSS believes that we can invite a controversial speaker to campus and provide a platform for her insights on environmental justice and community-based activism, without sponsoring every statement she makes.” (emphasis added)

That argument is interesting, as it suggests that speakers on campus should not be required/expected to present 100% factual information. Rather, it excuses the misinformation that it is well-known the paid speaker will present as “not sponsored”. But I question how does the audience, mostly with little agricultural background or expertise, discern which parts of the talk are “unsponsored untruths”, and which parts are “sponsored insights on environmental justice and community-based activism”? Could a similar argument be made that Dr. Andrew Wakefield should be invited to discuss his discredited contention that vaccines cause autism? I am reminded of the old adage, ‘You are entitled to your opinion. But you are not entitled to your own facts.’ I wonder, does sponsoring a speaker known to spread misinformation on university campuses serve the public good?

More generally, I am not sure that rationale would fly too well at faculty recruitment interviews, “Well 80% of what the candidate said was true but the remaining 20% about “pick your controversial polarizing scientific topic” [climate change not happening/ vaccines causing autism/the earth being flat/GMOs being unsafe to consume/evolution being a conspiracy] are stances not supported by the scientific literature, and this university does not endorse those fabrications as fact, but the candidate has a big public following so they seem like an acceptable hire.”

As an educator, I have a pretty simple expectation for speakers on university campuses, irrespective of their subject matter area. And that is they should not intentionally mislead people with anecdotes that are not supported by the scientific literature, or spread misinformation that they know to be false. And if I suspect this might be a problem, I would pair them with a public sector subject matter expert who could challenge any unsupported statements with evidence. That does not seem like a very high bar to me. And in my opinion, when it comes to encouraging community-based activism around shifting agricultural production practices in the face of climate change, that expectation for evidence is doubled because of the dramatic real world implications of ill-advised shifts based on incorrect information.