I have a paper entitled “Addressing the 2050 demand for terrestrial animal source food”, in @PNASNews Special Feature on the Sustainability of Animal-Sourced Foods and Plant-Based Alternatives., published today. This Feature includes several articles that consider the sustainability implications of replacing milk, meat and eggs with alternative proteins at scale. The significance statement (aka the bottom line) of my paper is as follows:

“Low- and middle-income countries house 76% of the global cattle herd, and by 2050 will be home to 8 billion people. They are the projected epicenter of both increased animal source food demand, and livestock-related emissions. The most promising approach to address this demand while limiting greenhouse gas emissions is to improve the efficiency of livestock production systems in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia through interventions in genetics, feeding and health. Boosting livestock productivity can improve both food security and producer incomes. Alternative proteins may play a limited role in addressing projected demand, but currently most companies are located in high-income countries Moreover, given the multifaceted roles that ruminants play in global agri-food systems, the social, economic and economic trade-offs associated with replacing meat and milk with alternative proteins must be evaluated holistically.”

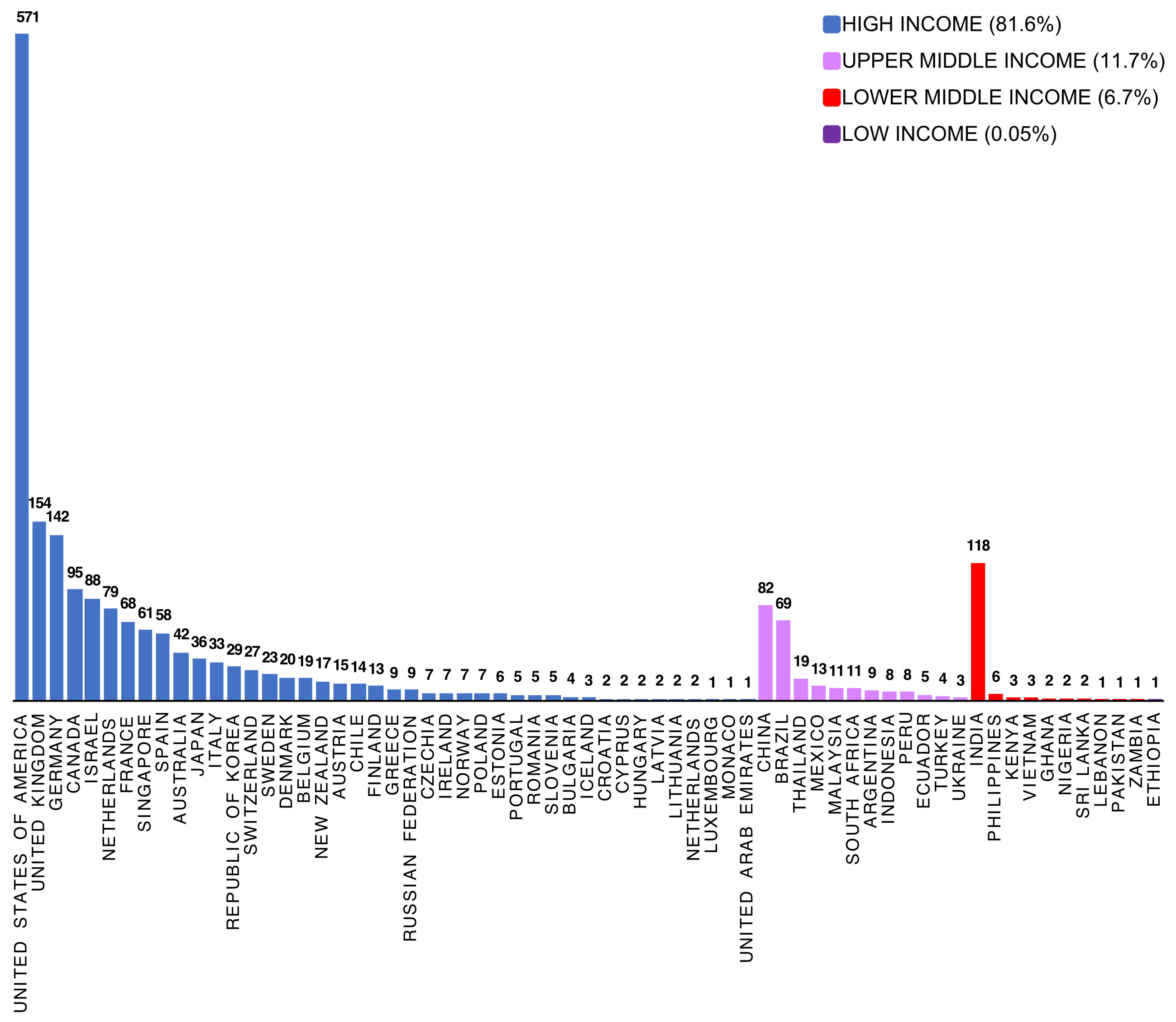

The deeper dive is that the high emissions intensity of terrestrial animal source food (TASF) and projected increasing demand in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) have spurred interest in the development of animal-free alternatives and manufactured food items that aim to substitute for meat, milk and eggs with the promise of reduced environmental impact of producing food. However, there is currently a mismatch between the location of these companies, and both projected increased TASF demand and emissions. To date, the vast majority (>81%) of companies proposing to produce alternative proteins are based high-income countries (Figure 1). The sustainability implications of replacing TASF with alternative proteins at scale needs to consider not only environmental metrics, but also the wider economic and social sustainability impacts, given the essential role livestock play in the livelihoods and food security of approximately 1.3 billion people in LMIC.

Figure 1. Global Distribution of Alternative Protein Companies (n=2,075) by World Bank Country Income Level Classification. Based on alternative protein company database containing 2099 records, maintained by The Good Food Institute https://gfi.org/resource/alternative-protein-company-database/ (Accessed 10/17/2024).

The developing world is the source of 75% of global greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions from ruminants, and will house 86% of the world’s human population by 2050. The adoption of cost-effective, genetic, feed and nutrition practices, and improving livestock health in LMIC are seen as the most promising interventions to reduce emissions resulting from projected increased TASF demand though 2050.

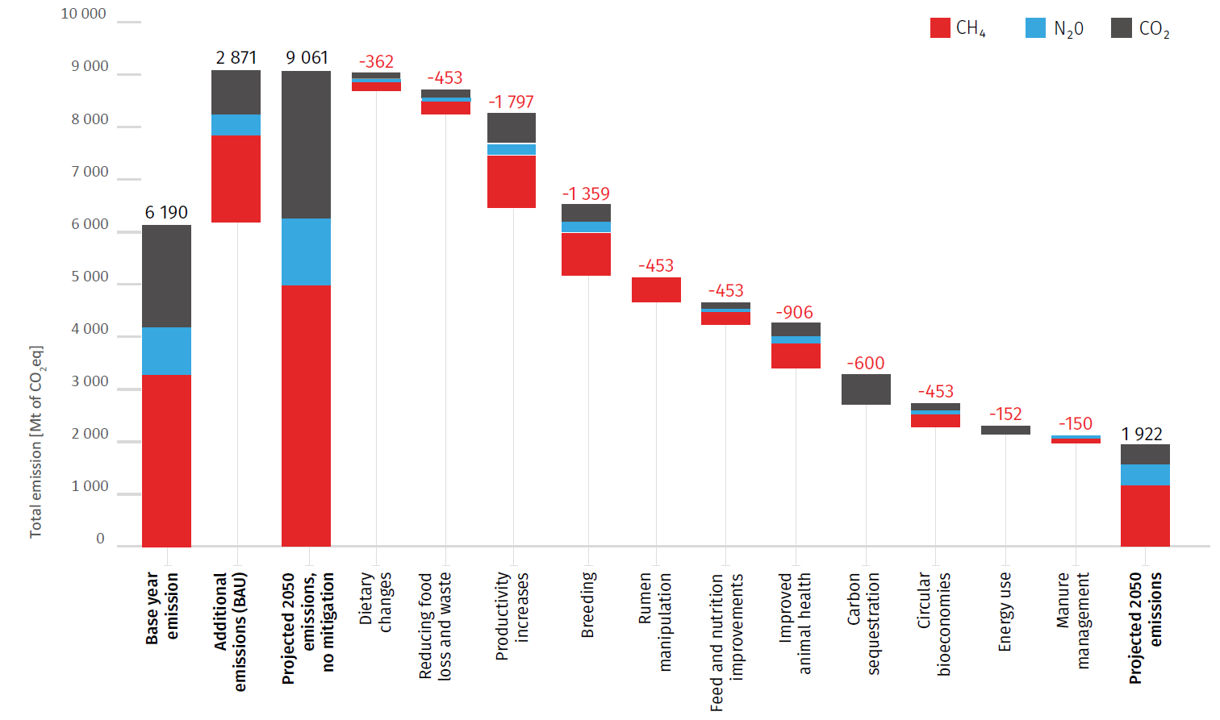

In 2023, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) released a report outlining that the most promising interventions to cumulatively reduce projected GHGs resulting from TASF demand by 55% though 2050, relative to a ‘business as usual’ no mitigation scenario (Figure 2). These included improvements in animal and feed management including productivity increases (20%), improved breeding (15%) and animal health (10%), adoption of known feed and nutrition practices (5%) and rumen manipulation with CH4 inhibitors including Bovaer (5%), see figure below . This report also suggested that dietary shift had a limited reduction potential (4%) based on the fact that in LMIC, the typical diet often has low GHG because it falls below recommended calorie levels and lacks sufficient proteins, fruits, vegetables and nuts. In those regions, a shift towards the recommended food-based dietary guidelines would be generally associated with increased overall consumption and a higher quantity of both plant- and animal-based foods.

Figure 2. Base year and projected emissions from livestock systems shown as a waterfall chart with a range of mitigation measures applied to 2050 with their technical potential. Reproduced from FAO (2023) Pathways towards lower emissions – A global assessment of the greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation options from livestock agrifood systems. (Rome). License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

There is general agreement that routinely consuming excessive amounts of dietary energy irrespective of the source definitively leads to poor human health outcomes (e.g. obesity), however the GHG implications of consuming more calories than recommended has received little attention. One Swedish study estimated that GHG emissions from metabolic food waste, defined as when energy intake exceeds the body’s physiological needs, amounted to up to 1.2 Mt CO2eq annually, accounting for approximately 2% of the total GHG emissions of Sweden. Similarly, a review of dietary strategies to reduce environmental impact, found that recommended diets had lower environmental impacts than typically-consumed diets, and that this was largely explained by the overconsumption of food energy associated with average diets. An Australian study estimated that the average diet resulted in emissions of 14.5 kg CO2eq per person per day, with more than a quarter of these emissions being derived from discretionary foods including alcoholic beverages, sugar-sweetened beverages, confectionary, baked and salted snacks, desserts, and processed meats . Additionally, these discretionary foods were associated with 36% of dietary energy in adult diets. In a follow up study, large differences (44-46%) in GHG emissions were observed between a higher-quality, lower-GHG-emission dietary pattern group and a lower-quality, higher-GHG-emission dietary pattern group. The main factor driving these differences was an increased consumption of energy-dense and nutrient-poor discretionary “treats” .

The discussion around TASF is frequently focused on a narrow subset of environmental metrics (i.e. GHG/unit weight of product) and first world consumption patterns, with little regard for locations where livestock underpin the necessities of life. There are a myriad of functions that animals provide in global food systems in addition to the provision of TASF, and these include supporting crop production with draft power and manure; providing a valuable use for crop residues and other by-products, generation of a regular income and employment especially for women, the provision of food security insurance and a form of savings; as well as fulfilling cultural and social roles. Efforts to promote sustainable diets need to be assessed using an approach that captures the triple bottom line of social, economic and environmental consequences. This is especially important in LMIC, given that these regions are the projected epicenter of human and livestock population growth, and concomitant increases in both TASF demand and livestock-related GHG emissions through 2050. Improvements in animal genetics, health and feed management are seen by a recent FAO report to be the most promising interventions to cumulatively reduce projected GHG resulting from TASF demand though 2050.

The full article can be obtained at the following link A.L. Van Eenennaam, Addressing the 2050 demand for terrestrial animal source food, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 121 (50) e2319001121, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2319001121 (2024).