Who does fund university research?

This is follow up to my BLOG last week about “Who should fund university research”? I thought it might be illustrative to examine actual data from my university. Not surprisingly for a large enterprise, UC Davis tracks sources of all monies coming into the university, and oversees the expenditure of such funds.

There are two basic ways research funding can come into the university – as a formal contract or grant, or as a donation. In the former case, there is some type of a grant application or description of work to be carried out (but not what the results of the research will be!!!) for which the funding is provided, in the second case it is what is called an “unrestricted” donation. This is money that is directed towards an individual professor, program or department with no further specification as to what the money is to be used for. Of course such funding is still managed by the university, and can’t be used for a vacation to Hawaii. Often it is used as seed funding to undertake a professor’s favorite research idea, perhaps one that is a bit too “out there” and risky to secure traditional grant funding in the absence of supporting preliminary data. In that sense it is like a donation to your favorite charity, you donate the money because you like the type of work that charity does. However you cannot directly specify exactly what the charity is to do with the money you donated.

Grants and contracts

These are the monies that really run research programs. The total awards by calendar year at UC Davis is in the ballpark of $750 million (i.e. three quarters of a billion). That is a lot of money, but UC Davis is a big university with a medical school which includes a hospital, a veterinary school, and all of the colleges that make up the campus. If we pessimistically (realistically) assume a 10% funding rate of public research funding that means the UC Davis faculty are on average writing $7.5 billion worth of grants each year, and are successfully bringing in one tenth of that. And to reiterate these funds are used to support graduate students, buy research supplies, perform experiments and advance knowledge. UC Davis is a powerful economic engine for California, generating $8.1 billion in statewide economic activity and supporting 72,000 jobs.

The approximate breakdown for the $786 million received in fiscal year 2014-15 was $427 million (54%) awards from the federal government, and likely a big chunk of research funding is also from the state government. $66.1 million (8.4%) was awards from foundations, and $59.4 million (6.7%) awards from industry sponsors. I think that is an interesting point, that UC Davis receives more sponsored research funding from foundations than it does from industry sponsors. The School of Medicine received the largest share of research grants at UC Davis with $264 million (34%), followed by the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences at $155 million (20%), and the School of Veterinary Medicine at $114 million (14.5%).

Donations

This pool of monies is more modest than that brought in by grants and contracts. I could only get this data for fiscal year, rather than calendar year, but it is in the vicinity of $200 million. Now the question that perhaps has been asked most frequently is how much funding is coming from specific companies – specifically those associated with the so-called “Agrochemical academic complex”? That all depends upon how you define such industries, but let’s go with the so-called “Big 6”; that is Monsanto, Syngenta, Bayer, BASF, DuPont/DuPont pioneer, and Dow.

The following table has the breakdown of total grants and contracts, donations and those two figures totaled, and then the breakout of how much of that funding and the (percentage of total) associated with the cumulative funding coming from the “Big 6” in recent years. (The numbers differ slightly from those above due to fiscal versus calendar year accounting.)

| Year | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

| Grants/Contracts | 699,728,437 | 718,934,464 | 751,864,525 | 793,797,558 |

| From “Big 6” | 1,407,821 (0.20%) | 477,178 (0.07%) | 881,856 (0.12%) | 746,160 (0.09%) |

| Donations | 132,451,535 | 149,134,036 | 165,704,178 | 184,180,960 |

| From “Big 6” | 768,172 (0.58%) | 1,386,079 (0.93%) | 858,912 (0.52%) | n/a |

| TOTAL | 832,179,972 | 868, 068,500 | 917,568,703 | 977,978,518 |

| From “Big 6” | 2,175,993 (0.26%) | 1,863,257 (0.21%) | 1,741,768 (0.19%) | n/a |

So in summary, at what is arguably the number one ranked agricultural research university in the world, the proportion of funding coming from the “Big 6 Agrochemical academic complex” funders is approximately $2 million per year, well under one half of one percent of total research funding received by the campus. To put that in perspective, the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences alone has 330 faculty members and 1,000 graduate students . Two million dollars is approximately what it takes to fully fund ~ 35 graduate students for a year.

So what is the money being used for?

Not surprisingly most of the funding from the “Big 6” was associated with research working in plant sciences and entomology. Some went to the medical school because the search for “Bayer” also captured research funding sponsored by “Bayer Healthcare”. A number of the donations were to Cooperative Extension county-based advisors performing field research with various crops. And just for transparency, none of it was directed to my research program (which is not surprising as I work on animals not plants!). Some was earmarked for work in specific crops like figs, pistachios, strawberries, rice, onions, woody crops and viticulture. And that is not surprising because California grows hundreds of specialty crops. Noticeably none of these crops have commercialized genetically engineered varieties, and their breeding programs are mostly run by public sector scientists.The one thing California does not grow much of is large acreage corn and soybeans. We do not have the right climate and conditions for these crops, and there are high-value alternative crops that CA farmers chose to grow. As a result, UC Davis does not do much research in these field crops, and the university therefore does not get much industry research funding for work in these crops.

I would wager that the University of Kentucky, home of the Kentucky Derby, probably has industry funding supporting is equine science program, ’cause they have a huge equine industry in that state. In general when a university has an important industry in its state, that industry helps to support research at that state-located public university. And in the case of California there is an amazing number of agricultural commodities grown – the fruit and vegetable industry raises a cornucopia of varieties in the state, and UC Davis has renowned brewing and wine making programs. As an example, the brewing science program at UC Davis has received several sizable donations from industry, including the recent $2 million donation from the owners of the local Sierra Nevada Brewing Company. Cheers to science-based beer brewing and wine making!

How does this breakdown compare to other land grant universities?

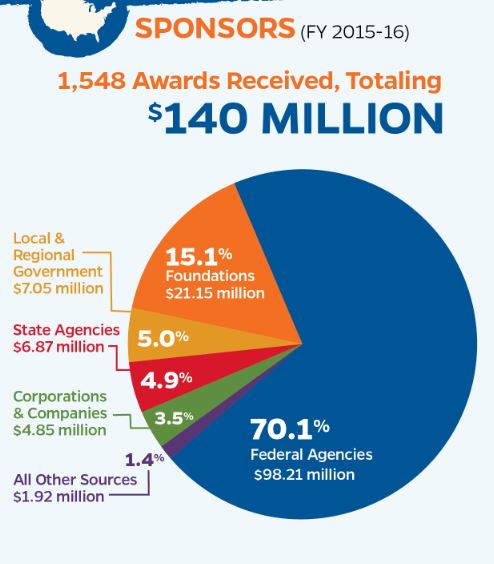

My colleague Kevin Folta at the University of Florida posted this useful graphic for the gators (University of Florida).

Funding to University of Florida FY 2015-2016 broken down by funding source

In the case of the University of Florida, the faculty brought in $140 million in sponsored funding in FY 2015-16, and of that 70% was from federal agencies, 15.5% was from foundations, and 3.5% was from corporations and industry. Kevin makes the observation in his blog regarding agricultural industry funders:

“They are frequently the beneficiaries of increased knowledge in agriculture, as well as the training and education we provide to the next generation of scientists”. I look forward to his next BLOG piece where he promises to write about whether industry support of science matters.

So there you have it – or at least a snapshot from two large agricultural universities as to which entities fund universities. By far the biggest source of funding is federal research grants – as might be expected at a public university.

Now I must go and focus my efforts on writing my next federal grant application – which unfortunately has a ~90% probability of not being funded and will likely only ever be read by 2 grant reviewers. As compared to this BLOG which has 100% chance of not securing funding for my research program, but hopefully will be of interest to more than 2 readers.