The following is an excerpt of a presentation I gave to the California Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Annual Conference and Exhibition 2016 in Riverside on April 21, 2016. The full paper which goes into MUCH greater detail and includes more scientific references is available on their conference website. Seemed an appropriate topic for my blog given Earth Day is tomorrow.

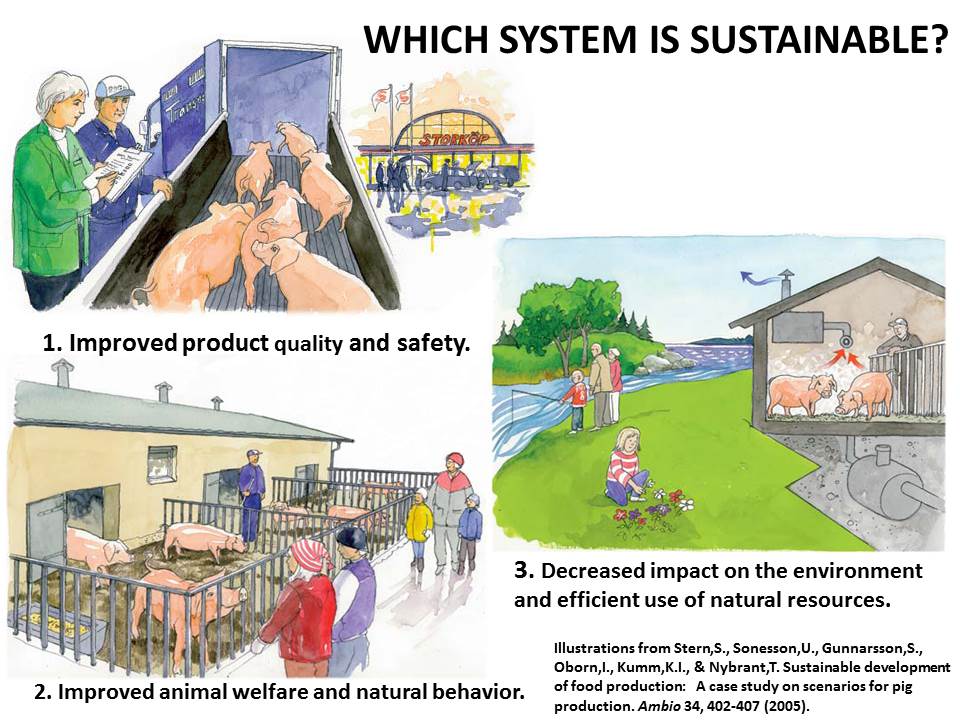

What is the “best” source of sustainable animal protein? There is no easy answer to that question. It all depends upon what sustainable means to you, and which metric(s) of sustainability you want to guide your decisions. Definitions of sustainability generally have to do with living within the limits of, and understanding the interconnections among, the three pillars of sustainability: economic, environmental and social. People put varying emphasis on these different pillars. Consider this graphic below – which is the sustainable system (1)? There is no one correct answer since it will depend upon the weighting you put on the various competing pillars of sustainability. There are pros and cons to each of the various scenarios.

Which system is sustainable (1)?

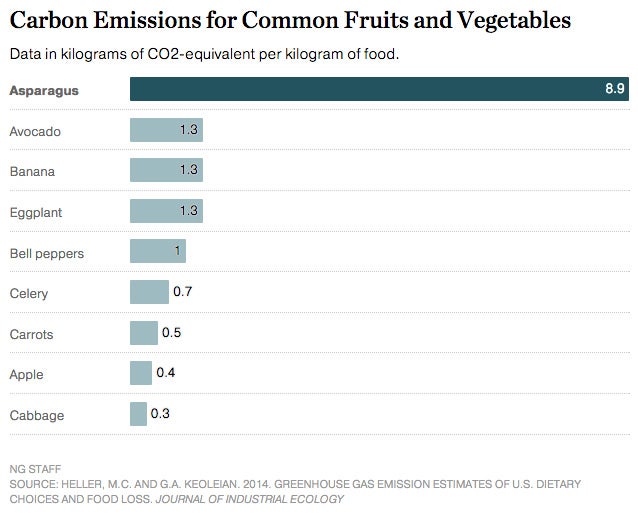

These tradeoffs occur more generally in all of our food choices. For example, some people swear by grass fed beef – but based on a carbon footprint per unit of protein perspective, it is much less efficient and therefore has a bigger carbon footprint per kg beef than intensively raised beef (2). Others advocate obtaining protein from nuts, but from a water footprint per unit of protein perspective they are more water intensive than all animal products (3). Others swear by wild-caught fish, but from a carbon footprint perspective, animal products from this source are very energy intensive if they involve bottom trawling and longline fishing (4). And let’s not even get into the issue of air miles which can make even the innocuous asparagus appear to be public enemy number one (5) based on CO2-equvalents per unit weight of food product as illustrated in the graphic below.

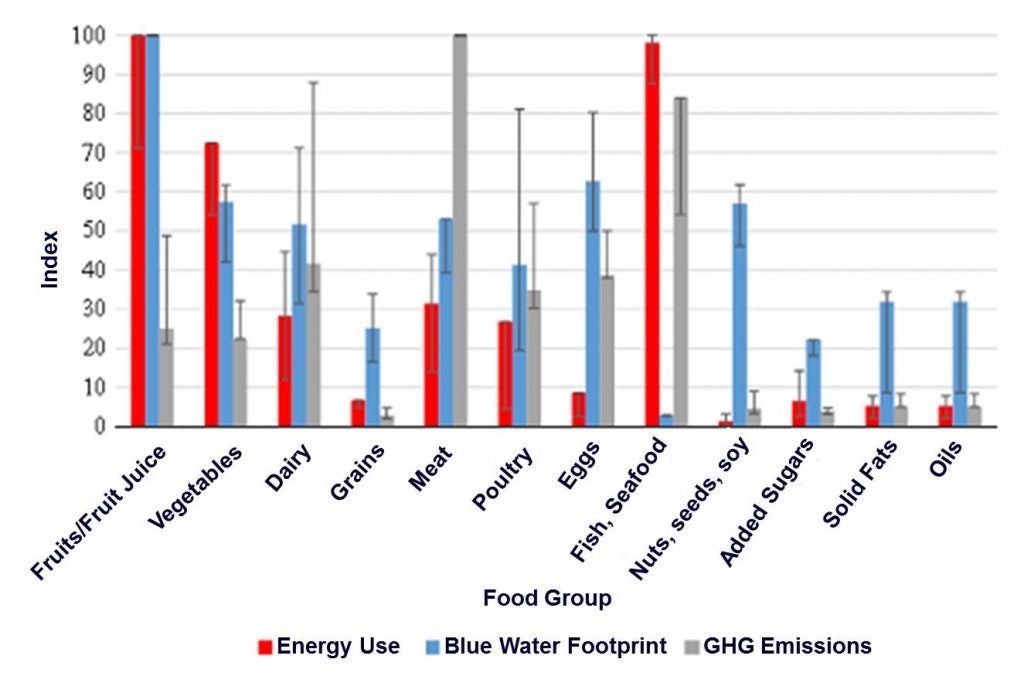

The sustainability question becomes even more complicated when considering the requirements for a nutritionally-balanced diet. Although it may seem like switching to a diet with less red meat and more fruits, fish and milk should be desirable from an environmental perspective, it may actually exacerbate climate change due to the relatively high energy and water use per calorie of these food products. A recent research paper (4) compared 3 different scenarios: 1) a reduced calorie diet (-300 calories/day) with the same mix of food as the average US diet; 2) the USDA-recommended food mix without reducing the total calories of an average diet; 3) reducing calories AND shifting to the USDA-recommended food mix. The first option resulted in a desirable 10% reduction in energy use, water use and emissions. The second scenario increased energy use (43%), water use (16%), and emissions (11%). Even when reducing calories on the USDA-recommended diet, the scenario 3 diet resulted in a significant increase in energy (38%), water use (10%), and emissions (6%) compared with the current status quo.

Why are the “costs” of these scenarios so different? Because fruit, fish, and dairy – as emphasized in the USDA guidelines – are foods that on a per calorie basis require the most energy and water to grow.

Input/emissions per calorie from some common US dietary items on calorie basis (6).

In contrast, added sugars, fats, oils, and grains require fewer resources and create fewer emissions per calorie. So although these might be the most environmentally-friendly sources of calories, they are not likely to be the ones that are recommended for consumption in large quantities as part of a healthy diet. If you totally forget health and consume a diet that would have the least impact on the environment, you would eat a lot more fats and sugars. Additionally, grains are also an excellent source of calories despite the fact they tend to be vilified in US dietary culture.

The bottom line is that food is more than calories and protein, and the dietary mix of foods and their availability will determine the best balance for a healthy diet. Adding in sustainability metrics complicates the discussion, and often conflicting results will be generated depending upon which metric is being optimized. Sometimes the most environmentally friendly diet might be the least healthy option. As with all discussions around sustainability, and agricultural production systems in general (organic, conventional, genetically engineered etc.), it is complicated and there are tradeoffs. Beware of anyone who touts a seemingly magic solution. There will never be black and white answers to the questions of which foods are the most sustainable, other than perhaps just eating less of whatever you are currently eating. Although this is a privileged first-world perspective, as evidenced by the approximately 25,000 people who die of malnutrition or starvation daily. As the saying goes, “A well-fed man (perhaps we could substitute society in here) has many problems (and food choices!), a starving man has but one.”

SUMMARY

There is no one sustainable source of protein, and depending upon the question that is being asked (e.g. carbon emissions/water use/land use/energy use per calorie/unit weight/unit protein), different food products will look like the “most sustainable” choice. There are also ethical and religious concerns around animal welfare and/or consuming meat and/or animal products (e.g. eggs, milk). Often there are direct conflicts between what is perceived as the most sustainable production system. Is it the one that best protects animal health/welfare, the one with the lowest environmental footprint per unit of product, or the most efficient? As with all dietary decisions there are tradeoffs among the various pillars of sustainability, and consumers will need to make the choices they consider to be best for their particular family values, budget, and circumstances.

REFERENCES

- Stern S, Sonesson U, Gunnarsson S, et al. 2005. Sustainable development of food production: a case study on scenarios for pig production. Ambio 34:402-407.

- Nijdam D, Rood T, Westhoek H. 2012. The price of protein: Review of land use and carbon footprints from life cycle assessments of animal food products and their substitutes. Food Policy 37:760-770.

- Mekonnen MM, Hoekstra AY. 2012. A Global Assessment of the Water Footprint of Farm Animal Products. Ecosystems 15:401-415

- Tom MS, Fischbeck PS, Hendrickson CT. 2015. Energy use, blue water footprint, and greenhouse gas emissions for current food consumption patterns and dietary recommendations in the US. Environment Systems and Decisions 2015:1-12.

- Heller, M. C. and Keoleian, G. A. 2015. Greenhouse Gas Emission Estimates of U.S. Dietary Choices and Food Loss. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 19: 391–401. doi: 10.1111/jiec.12174